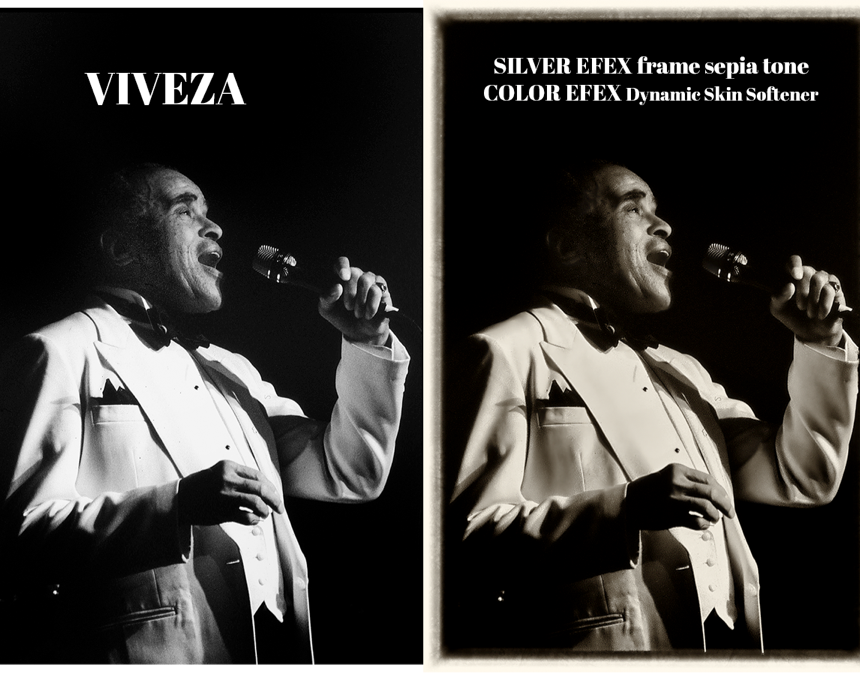

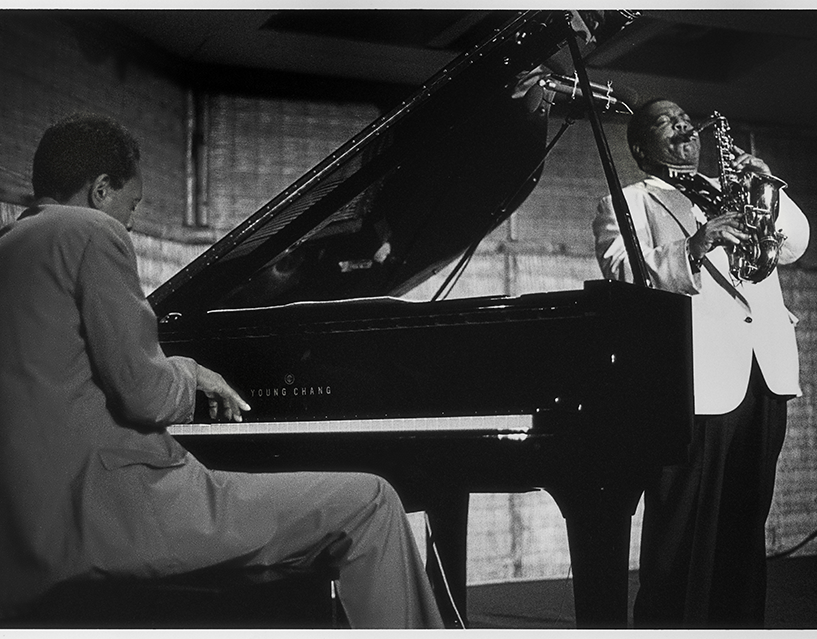

lft. Horace Tapscott rt. Arthur Blythe at The World Stage in Leimert Park, Los Angeles

Horace Tapscott is a prominent community figure. There are many reasons to applaud him. He helped nurture such talents as David Murray, James Newton, Arthur Blythe and others. Through his Pan African Peoples Arkestra, he provided a platform for exceptional musicians such as Roberto Miranda, Sun Ship Theus and Azar Lawrence who otherwise might have escaped the notice they deserved.

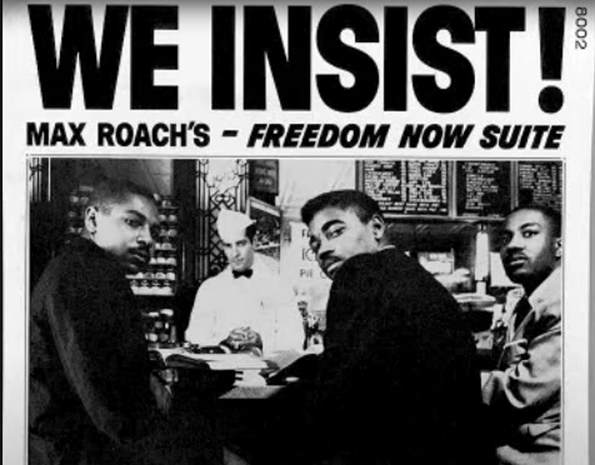

So dedicated is Horace to integrating art into the community, that he had the Arkestra playing in the middle of the Watts Rebellion from a flatbed truck "(Every Ten Feet was a Soldier: Jazz and the Watts Rebellion) ."Kids were dancing in the streets until the police showed up with their guns drawn and forced the thirty musicians, dancers and poets to stop." A conventional society's reaction to innovation, something Horace has had to endure for almost half a century now. Despite the lack of recognition and record sales, he has achieved in the arena that matters most. "Your record might not be in the top ten but your life is." If you ask Horace he is merely returning the favor.

"It all started out of Robert and of Mary in Houston, Texas in 1934. I was raised in a home that was filled with music. My mother was a Jazz pianist and tuba player. A friend of Floyd Dixon (of Hey Bartender fame), she wouldn't let me out of the house till she heard something. There was always a sacrifice made so I might move on towards the types of music I wanted to explore. In 1943 we migrated to Central Avenue in the heart of L.A. about two blocks from the Black Musicians Union." (The Los Angeles Musicians Unions were segregated until 1953)

Central Avenue was the equivalent of New York's famed 52nd Street. Not only was there homegrown talent such as Dexter Gordon, Lester and Martha Young, Wardell Gray, Chico Hamilton and Sonny Criss. But all the stars of the day, Charlie Parker, Howard McGhee, Slim Gaillard, Earl Garner and Teddy Edwards, would be jamming at regular and after hours clubs till the wee hours of the morning. Clubs with colorful names like The Bucket of Blood, Casablanca, Cobra Room, Jacks Basket Room, The Jungle Room and Cafe Society were strung out from 1st to 97th streets. Filled to overflowing with a heterogeneous crowd composed of everyone from locals to local stars like Eva Gardner. Everything was moving west with the war and the industry that was being created around it.

For Horace Tapscott, the musicians that mattered were not only great players but also great teachers. There were four that stood out among the fine teachers at the time. Miss Elma Hightower, whose band could be seen marching down Central Avenue every Saturday morning, boasted among its alumni, Vi Red one of the jazz's pioneering female big band leaders. Lloyd Reese was a profound influence for most of the young sax players of the time. Included among his disciples were a couple of youngsters by the names of Eric Dolphy and Dexter Gordon. Horace credits Gerald Wilson and to a smaller extent trombonist Melba Liston with "taking me off the streets and really getting me to play the instrument." (The trombone was the first instrument he played professionally. An auto accident and the resulting dental surgery forced him to give it up) And finally Samuel Brown who tutored Dexter, Sonny Criss, Chico Hamilton and most important for our purposes here had the most lasting effect on Horace and his work. "Samuel told me, 'I'll teach you if you promise to pass it on.' And he did."

"I lived within shouting distance of the 'union' which was this giant three story house. I was blessed. I was into it all day everyday with all the cats you could name. The major people were Sam Brown at Jefferson High, Gerald Wilson and Lloyd Reese. I even went to night school and studied improvisation with Buddy Collette. I played in the municipal orchestra that consisted of Eric Dolphy, Frank Morgan, Walter Benton, myself and a bunch of older musicians that had been around for years. In addition I was playing with my own group at the Bucket of Blood on Vernon. In 1952, I went into the Air Force Band with Houston Person and Billy James. There all I had to do was write and perform with the orchestra. It allowed me to develop because I had a forum for my ideas, and quality people to carry them out.

When I got out of the Air Force I went on he road with Lionel Hampton's Band. I was dissatisfied with the experience because it mainly consisted of one nighters with little or no feedback. A sort of machine-like existence. When we got back to Hollywood I got off the bus and stayed home."

What Horace found at home amounted to mass neglect by the local media. With the exception of Leonard Feather, most of the writers still hovered about the "Big Apple" as if it was the only breeding ground for genius. "Most of the writers that were here expected to be wined and dined for their efforts on our behalf." So Horace went about developing a solution that didn't force him to rely on the whimsical patronage of this press or the powers to be in the music business.

"The only thing to do was to organize the musicians among themselves and bring music to the people. To change the image of Jazz and those who played it, you had to show them that the music came from them and their surroundings. You had to be consistent. Not just a day in the park. So we formed The Underground Musicians Union (which later became UGMAA, The Union of God's Musicians and Artists Ascension) in 1961 with five people. Despite the fact that the Pan- African Peoples Arkestra, which is the musical voice of UGMAA, has provided a platform for young musicians and composers like David Murray, Patrice Rushen and Arthur Blythe only one recording (Flight 17 on the Nimbus label) was ever made.

“The reason we took our music to the schools, churches and the streets was because we couldn't dictate terms to the music center."

At The World Stage

His first "major" recordings were a set of two albums Sonny's Dream, which featured Sonny Criss on Prestige and The Giant Has Awakened, Horace's debut as a leader, on Flying Dutchman Records. The Giant Has Awakened, which also marked Arthur Blythe's recording debut, reflected the angry and turbulent years. As intense as his playing gets however, he never loses the art of it. In the same manner as one of his acknowledged influences, Vladimir Horowitz he digs in and "grabs hold of the piano." His passionate approach to life may also have been responsible for a life-threatening cerebral aneurysm he developed in 1978. "It was from all the things I was concerned with at the time." The doctors gave him an even chance of recovery. Less comforting was the fact that the other four men in his ward with the same condition didn't make it. Horace describes his mystical recovery to writer Gregg Burk, "During the operation, I left my body and saw the doctors below me."He says he saw many who died in past years hold out their hands to him, "Like, you can come if you want to. But aren't you thinking about the Arkestra?" When he awoke he found that he could move his fingers and he could play but for three years that was all he could do. His recent album "Dark Tree" is a triumph. A beautifully recorded live album it features a universe of expression from the beautifully tender "A Dress For Renee," to the piano moving rhythms of "Dark Tree." Once again the recognition and acclaims that he has received abroad has translated into an opportunity well advantaged.

Always a master at making a bottom heavy sound move, here he combines a powerful left hand with Cecil McBee's powerful bass lines. His Arkestra boasts four to five bass players (Roberto Miranda sounds like two) and three drummers.

Horace Tapscott has endured. Perhaps now he will prosper. He has a song called "Middle Aged Madness" that he dedicates to "all us teenagers in our fifties who are too old for this and too young for that. Most of the musicians didn't make it here. You have to hurrah when you get this far. Maybe you should get an award for surviving tactics. It would be more meaningful than a Grammy. For me it's been from here to there, filling in with transcribing, teaching and ghost writing. Maybe it'll change now. I just thank God for all the people who have been around for me and had enabled me to contribute to change the image of jazz." And we thank you Horace for being around for us.

His groundbreaking compositions and orchestral work is finally becoming available through the efforts of Hat Art Records, Dark Tree Volume 1 & 2 with John Carter and Cecil Mcbee. Nimbus Records has released a seven record set entitled The Tapscott Sessions and RCA Novus has recently made available West Coast Hot; a re-release of Bob Thiele's Flying Dutchman Sessions with John Carter.