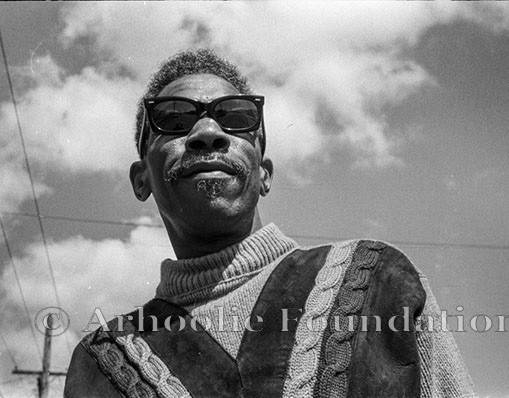

Photo by Esther Kutnick

Keith Jarrett Shifting Musical Gears

By Bob Hershon

Originally published in Jazztimes February 1987

San Francisco—Keith Jarrett is in town for the Speaking of Music series. I’m sure many of his followers thought he would unlock the secrets of pieces like those contained in the Koln concerts. They'd go marching out the door with a lexicon of harmonies, melodies and licks that would last them a lifetime. He was indeed speaking of music, but the secrets he unlocked were about himself.

The music of musicians such as Keith Jarrett, is less about the sum total of their technique than of who they are and what they feel. The barrier to overcome is not one of manual dexterity but, as Jarrett points out, "It is to bypass what's between your intuition and the result you desire." For a time Keith Jarrett’s music has shifted focus. In his newest album Spirits, ECM I333/4 (Double Album), the piano has moved from center stage. The spotlight has been given over to the primitive but powerful sounds of instruments such as the tabla, recorder, and flute. The harmonies we have grown lo love arc still there, but everything has been simplified.

“You can’t get close to a complex thing like the piano, as you can with something you can touch directly like the flute. The piano plays a subordinate note. It’s on the tapes; I’m not in love with the piano. I think of it as too sophisticated an instrument for what I’m doing.

I go to Japan and I have my one or two days of jet lag before I do my concerts. And I walk into any shop, any building, anywhere they're playing “new age” music. I get so tired of the piano being in Japan, that I can't get used to it any more."

These latest recordings reflect an internal change that Keith Jarrett experienced in I985.

“The genesis for the change was a breakdown that I had in May I985, which was symbolic in many ways. I had a classical career that had finally been accepted by the so-called critics and-called musicians. It was then I realized that this wasn't what I was meant to do. It wasn't that I was doing the wrong things. It was just time to do something else, and that was to start making music, instead of playing music. And when I started picking up these instruments something happened. My original reason for making music became even more important. There was no sequence to these recordings. I used two cassette machines, bouncing the tracks back and forth. If I heard a tabla, I would play a tabla and not what instrument or arrangement would come after that. I had played recorder before, but not the flute. I played better than I can play. When your intent is pure enough, you can do what you intend despite your technical limitations.

These recordings are in stark contrast to the classical pieces by Bach, Bartok and Barber that Keith has been performing over the past few years. In Spirits the idea was not to prepare.

Transformation

"I worked for a year on a piece by Samuel Barber to give three performances. If I am going to work over a year on a piece to play it three times, there's got to be something better I can do in that time. I found in a month I could have three hours of music unrepeatable even by me. There's a purity that's impossible to get by a repeated anything. As a result of having to guess at the right levels, there were several occasions when I had to do something over and I could never do it over. The first take was it."

The seeds of Jarrett's transformation could be seen in "Elegy", an orchestral piece that he had written the summer before. After only a brier hearing of the "Elegy" it has replaced “Arbour Zena" and "Luminescence" as my favorite among Keith Jarrett's orchestral works.

“I think this piece was a prelude to releasing myself from who I was supposed to be. The Elegy was nothing but a sketch of melodic content that just seemed to flow from my pen. I don't know why I liked it so much, because there was nothing really there. I was doing one of these Japanese concerts, which happen once a year when I have my own evening. And they were going to do my Oboe Piece and a sonata I had written for violin and piano. There was room for another work on the program. So quick as I could - quicker than I have ever before - I wrote this out for violin and string orchestra and they put it into the program and I realized it was an elegy for my grandmother. I was not afraid to let it be what it was without caring if it sounded like a piece of mine should sound. It was the beginning of letting go of things."

The focus of these tapes also moves away from technique. I asked Keith if he put the piano in the background because he already had the most ingrained technique for it.

"Technique is nothing. It can supplant what's really there. If someone has something to say and they have a script, they don't have to think tor themselves on the spot. We live like that. We have our personalities and they are our script. But music and communication of anything should come from zero. For example, I just wrote a piece for the American Indian recently played by Richard Stolzman, Paula Robson, Fred Sherry and myself. At the last minute I felt there should be some percussion instruments in this piece. I took them into rehearsal and one of the first things to happen was that Richard Stolzman, one of the better classical clarinet players in the world, forgot to come in where he was supposed to because he liked ringing his bell. Fred tapped him on the shoulder with his bow and said "Rich"? "Oh, I'm sorry." Stolzman said.

I said, "Please don't say you're sorry. We’ll change the passage." He said "Please don't change it for me.” I said, I'm not changing it for you, I'm changing it for the bells." That showed me that anybody at any level of proficiency could suddenly remember that music doesn't have anything to do with how well they play their instruments."

If the reaction of the audience here at the Speaking of Music series where the tapes were premiered is any indicator, many fans will be shocked. At the moment that a musician takes a step that brings him closer to his source; he takes the risk of leaving many of his fans behind.

“Life is hazardous. When we try to live appropriately to who we were yesterday and continue to think that would be correct for us tomorrow, we take a bigger risk of losing consciousness and falling asleep. When you take the risk of being conscious you can’t count on support. The only way I can play these new tapes tonight is because I know how alone I am, and come to terms with that. It’s being alone and being insecure that seems to quash everyone’s actual creative attempts, because their attempts are only out of insecurity. There is something that really gets under my skin. A lot of people yawn when I'm not talking about voicings or how I played this or that. To be potent in music you have to talk and think about issues like this. Music is not about music. It's like saying a book is about a book. It’s about something that transcends the mere playing of music.

Keith Jarrett’s fans can probably expect more Standards albums, as there is a great deal of recorded and live music in the can. Spirits may only be a passage, for its unlikely he ever seeks the safety of any style again.