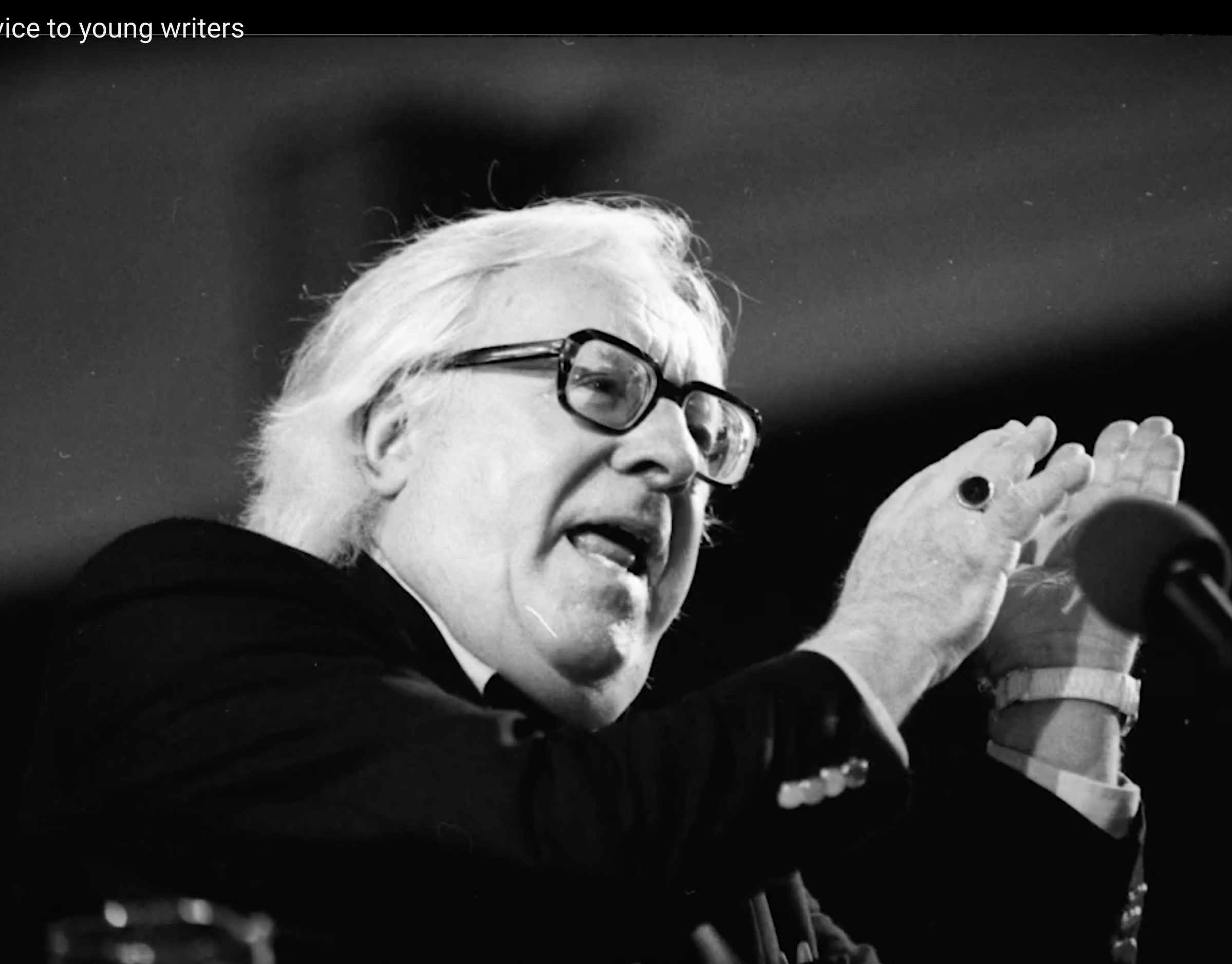

Smiley Winters

Pianist Ed Kelly summed it up the best, “He was the godfather of us

all. When Pharaoh Sanders, John Handy and I were getting started he was

our guru.” If you ask Smiley he was happy playing the music he loved

for the people who could appreciate it, while “rooting the youngsters

on”. “I wasn’t overly concerned with how popular I was with the general

public. I played for other musicians.”

all. When Pharaoh Sanders, John Handy and I were getting started he was

our guru.” If you ask Smiley he was happy playing the music he loved

for the people who could appreciate it, while “rooting the youngsters

on”. “I wasn’t overly concerned with how popular I was with the general

public. I played for other musicians.”

Article originally published in California Jazz Now Magazine in

1992

1992

Writing this article turned into a chore of indescribable proportions. Every time I talked to Smiley, Ed Kelly or some other “living “historical source, I would be deluged with scores of names and dates covering a decade or two, of a history I was totally ignorant of. What I ended up doing, was analogous to cramming for a final from a book of history I never opened. Then I realized it took Smiley and a score of musicians, 40 years to make this history, so how could I be expected to chronicle it in a couple of weeks. California Jazz Now was created to shine a light on the resident musicians of the “Golden State” who are not getting the plaudits or ink they deserve. SF Bay Area more than L.A. seems to be, the best kept family secret. To remedy this we will feature such names as Robert Porter, Oscar Dennard, Frank Haynes, Phineas Osborne and others in future issues.

Born in 1929 in St. Louis, William “Smiley” Winters was given his first lesson in the importance and variety of rhythms from his mother, who was at one time the most popular cakewalk dancer in town. Though Smiley gained valuable knowledge from blues musicians such as Harry Wynn and Eddie and The Blue Devils; it was an appearance by Charlie Parker that really turned him around.

“I heard Bird when he came to town with Jay McShann and it ruined my mind. To most people it was scrambled eggs but to me it was beautiful music.” It wasn’t till he joined the Navy in 1945 (at sixteen!) that he had his first encounter with “real musicians”. “The highlight of my

time in the service was playing in Jerome Richardson’s band St. Marys Freeflight in Port Chicago. My career slowed down after that. I couldn’t tour anymore because I had ten kids from1945 t0 1955. Now I have twenty grandchildren, one great grandchild and two on the way. I did spend some time at the Onyx Club in New York and Kelly’s Stable, played with Billie Holliday in Honolulu but I couldn’t stay there long.” So Smiley chose to stay at home developing his musical skills while nurturing the Bay Area jazz scene.

time in the service was playing in Jerome Richardson’s band St. Marys Freeflight in Port Chicago. My career slowed down after that. I couldn’t tour anymore because I had ten kids from1945 t0 1955. Now I have twenty grandchildren, one great grandchild and two on the way. I did spend some time at the Onyx Club in New York and Kelly’s Stable, played with Billie Holliday in Honolulu but I couldn’t stay there long.” So Smiley chose to stay at home developing his musical skills while nurturing the Bay Area jazz scene.

As trumpeter Robert Porter pointed out, Smiley Winters was in the vanguard of drummers at the time. “His concept was as advanced as Kenny Clarke’s. His hands were well schooled and faster and more lyrical than most.” Smiley’s advanced concepts did not earn him praise from the rhythm and blues and commercial gigs he was using to pay his bills. “They’d say play rhythm, Smiley, rhythm. I’d say no I hear the melody. I lost a lot of gigs that way. I developed my concept by listening to “Baby” Dodd’s and a drummer called Battle Axe who I thought was even further out than Kenny Clarke. I learned Gene Krupa’s book and studied Count Basie and Duke. I tried to get something out of everybody I heard even Bob Wills. I felt that jazz was something you had to breathe and live. It was not just an intellectual exercise you made up your mind to do. It was a total commitment.”

Though Smiley Winters couldn’t tour or travel with the top musicians of the day he ended up playing with them all. From the late forties the Bay Area was host to a club scene that would rival even New York. The Palladium and the Bar None in Oakland numerous blues clubs in Richmond where talents such as Jimmy McCracklin and T Bone Walker played. And in San Francisco Streets of Paris, Soulville, Bop City, The Jazz Cellar, The Plantation and Jackson’s Nook provided Smiley the opportunity to play with Dexter Gordon, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Billy Eckstine, King Pleasure, “Ben Webster, Sonny Stitt and of course Charlie Parker.

I played with Bird at Bop City along with Al Hibbler. All you had to do was follow Bird. He would never squawk about what you did behind him. It was easy because he carried his own drum in his back pocket. A lot of people rode off his back. I did. I sounded the best I ever did with him. Bop City was a great place. Jimbo the owner used to run around town gathering up all these musicians and actors like Clint Eastwood to fill his club. Ringo Starr once spent an entire set sitting next to me watching me play drums at Bop City. Maybe my favorite playing experiences were with Sonny Stitt. As great as he was, he always made an attempt to fit in with you instead of you fitting in with him. It was like electricity every time you got on the same stage. He knew all the music, your part and his.” Ed Kelly recollects playing with Sonny and Smiley,” If you got lost Sonny would yell, “What’s your name? Kelly,that’s cm7!” Smiley Winters, “It was too bad Sonny Stitt didn’t get the recognition Bird did; it was really a case of two different people getting the same message at the same time. I also enjoyed my time with Dinah Washington; it surprised me she picked me up. She had Joe Zawinul and Jimmy Rowles in her band at the time. She had the beautiful, earthy sound of a gospel singer which many singers like Patti La Belle have imitated. She was also was an accomplished cello and organ player. I always loved jazz because it was always changing. Though some people resisted acknowledging change as some players who took off in new, directions, I thrived on it.”

“For instance, I had no problem playing with Ornette Coleman over on Haight Street despite having no time to practice. He made perfect sense to me. I love all forms of art that challenge the eye or the ear. There is a group of modern sculptures by the Broadway Bart stop in Oakland that I feel has changed the entire atmosphere of the setting. Music can do the same thing.”

Though I could continue to list the endless associations Smiley made with great musicians, who for the most part sought him out, there is a whole other side to his career. In the same mold as Art Blakey he was a great teacher as well as a promoter of young musicians. It was Smiley

who kept urging a shy young horn player by the name of John Handy to exhibit his talents on the stage of places like Bop City. “I always thought he was a good player but he always listened and went home and practiced till he was sure of his abilities.” It was Smiley who

encouraged a young Pharaoh Sanders to take up with John Coltrane even though Pharaoh had grave doubts about the offer. At one time he provided young musicians with a rhythm section to practice their chops with. Besides Smiley on drums it would often include musicians like

Jessica Williams on piano. Besides his unique methods it was the respect and understanding he afforded younger players that caused him to be in demand. One of his more successful students Benny Green explains, “I met him when I was fourteen at Cazadero. Though he was seasoned he was never condescending. He would also offer you a chance to play with other veterans. He had an uncanny knack of nurturing potential. Any criticism he offered was constructive, like learning a tune in all twelve keys instead of one; or teaching me to caress every beat.”

who kept urging a shy young horn player by the name of John Handy to exhibit his talents on the stage of places like Bop City. “I always thought he was a good player but he always listened and went home and practiced till he was sure of his abilities.” It was Smiley who

encouraged a young Pharaoh Sanders to take up with John Coltrane even though Pharaoh had grave doubts about the offer. At one time he provided young musicians with a rhythm section to practice their chops with. Besides Smiley on drums it would often include musicians like

Jessica Williams on piano. Besides his unique methods it was the respect and understanding he afforded younger players that caused him to be in demand. One of his more successful students Benny Green explains, “I met him when I was fourteen at Cazadero. Though he was seasoned he was never condescending. He would also offer you a chance to play with other veterans. He had an uncanny knack of nurturing potential. Any criticism he offered was constructive, like learning a tune in all twelve keys instead of one; or teaching me to caress every beat.”

“I’m really satisfied with the way things turned out. My brother once

told me if you’re not the best always be with the best. So I’ve been

with the heaviest of cats. And I think it allows me to offer students

something that they can’t get out of those books. I can tell them how

Bird really worked a piece out. Which I think is far superior to any

chart. It’s important to keep a continuum with the past otherwise you

end up with just so much empty knowledge.

told me if you’re not the best always be with the best. So I’ve been

with the heaviest of cats. And I think it allows me to offer students

something that they can’t get out of those books. I can tell them how

Bird really worked a piece out. Which I think is far superior to any

chart. It’s important to keep a continuum with the past otherwise you

end up with just so much empty knowledge.

It’s always been my dream to create my own jazz school where I could pass this on.”

You already have

William “Smiley” Winters, you already have.

William “Smiley” Winters, you already have.